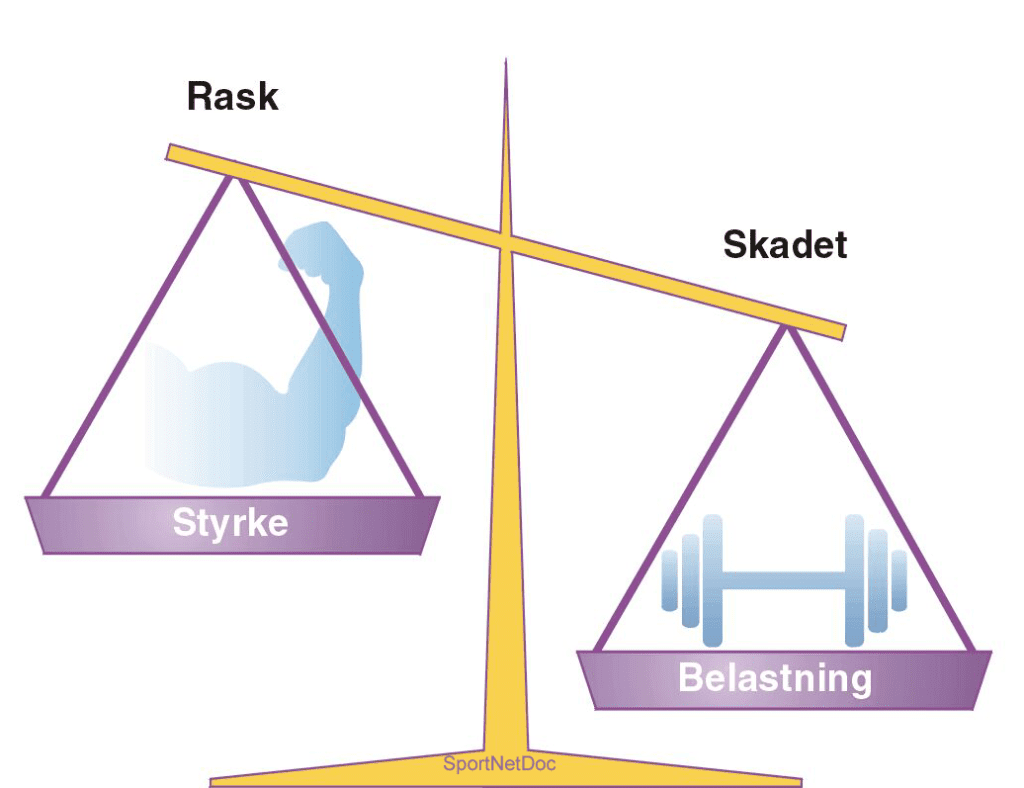

In simple terms, sports injuries occur when tissue is subjected to stresses that exceed its strength.

The imbalance between tissue strength (training condition) and load is crucial in understanding sports injuries, how they occur and how they are treated and prevented. The risk of injury (re)occurrence is therefore reduced not only by reducing load, but also by increasing tissue strength.

This means that injured tissue (muscle, tendon, ligament, bone) must be relieved, but at the same time controlled strength training must take place so that the tissue can become even stronger than before the injury occurred.

The injured athlete should therefore do general conditioning, strength and flexibility training as well as specialised training to slowly increase the strength of the injured tissue. Injured athletes should not necessarily train less than healthy athletes for the above reasons.

The main cause of overuse injuries is overload, but poor equipment (e.g. poor running shoes), incorrect technique or inappropriate training (e.g. increasing training intensity too quickly) can contribute to the onset of injury. Of course, it is essential to change these conditions, otherwise the injury will quickly recur after an injury break.

‘If you hit your head against the wall 100 times a day, you'll get a headache. You can get treatment for this, but if you keep banging your head

the wall 100 times a day, the treatment won't help!’Dr. Ulrich Fredberg

Many sports injuries are caused by overuse due to incorrect (re)training. It takes 4 weeks of training to affect muscle strength, 4 months of training to affect bone strength and 8 months of training to affect ligament and tendon strength. Rapidly increasing training intensity and training volume will therefore quickly increase the strength of the muscles and thus the load the muscles will transfer to tendons and bones. However, tendons and bones are not yet trained to cope with this increased load, resulting in overuse symptoms from bones (e.g. shin splints, fatigue fractures) or tendons (e.g. Achilles tendonitis, jumper’s knee etc.). To prevent overuse injuries, the amount and intensity of training should be increased slowly so that muscles, bones and tendons can adapt to the increased load.

When an injury occurs in the tissue, this usually results in bleeding and fluid leaking into the tissue. The bleeding and swelling causes pain. In acute injuries, the bleeding is so severe that swelling and pain quickly follow. In overuse injuries, the bleeding and fluid leakage in the tissue is so modest that soreness often only occurs several hours after the strain (in the evening or the next morning). However, this soreness is an important signal that the tissue has been stressed more than it was trained for and that a minor injury has (re)occurred. If training is changed immediately, a few days of reduced training is often sufficient for the symptoms to subside. If no change in training is made, the strain will continue and the injury can develop into a long-term chronic injury within days to months, making it impossible to participate in sport for six months to a year. It is therefore crucial that the athlete learns to listen to the signals from the body and modify training as soon as pain occurs. All rehabilitation should therefore take place within the pain threshold.

The rehabilitation of sports injuries is divided into 2 parts:

1. part consists of relieving the injured tissue (ligament, tendon or muscle) as long as there is swelling or pain. It is important to avoid breaks without training. You should therefore continue training all muscles and joints that are not injured. It takes much longer to build tissue with exercise than it does to break down tissue with total offloading.

‘One week off costs 3 weeks of rehabilitation’.

Therefore, it can take several months to rebuild fitness after a ‘3-week break’. Breaks often bring pain relief, but at the same time weaken all muscles, tendons, ligaments and bones, which means there is a significantly increased risk of rapid recurrence of the injury when training resumes. While the athlete is offloading the injured tissue, it is almost always possible to continue:

- Fitness training (cycling, swimming, possibly running for arm and upper body injuries)

- Strength training of all non-injured muscles

- Technical exercises

- Preventive flexibility training and coordination exercises

Part 2 consists of specific rehabilitation of the injured tissue with the aim of making it strong enough to withstand the load required by the sporting activity. To minimise the risk of re-injury, the tissue must of course be even stronger than before the injury occurred. Specific rehabilitation should only begin 24-48 hours after the injury has occurred (to avoid the risk of worsening the bleeding).

Rehabilitation should be seen as an attempt to climb a ladder, where the intensity and possibly the amount of exercise is increased step by step. If exercising at a certain level does not cause pain during or after exercise (even the day after), you can move up to the next level of exercise. Take one step at a time. If that holds (no pain), take one more step and so on. If you get impatient and rush your rehabilitation and skip steps, you risk ‘falling off’ the ladder and having to start all over again, perhaps even with an injury that is further aggravated.

This type of relief is called ‘ACTIVE REST’. In certain special cases, medical treatment can shorten the relief period.

Training ladders

You risk – as in ludo – being ‘beaten home to START’.

If you experience pain or swelling during or after training, REMEMBER that this is a signal that ‘this is the limit of what the injury can currently withstand.’ If you ignore the warning and continue up the training ladder, you will exceed the limit of what the tissue can withstand and there is a risk of aggravating the injury. The load should therefore be reduced (but not stopped) over the next few days (‘climb a few steps down the ladder’) and continue training at this slightly less strenuous level. After a few days, when the pain has subsided, try slowly increasing the load once again.

If you do heavy strength training, it can be beneficial to have a day of recovery between workouts.

Medical treatment does not favour the progress of the second part of rehabilitation, as no legal means will be able to increase tissue strength. This can only be achieved through sensible training.