Anatomy

The bones of the knee joint include the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone) and patella (kneecap). The articular surfaces of the femur, tibia and patella are covered with a few millimetres of cartilage that serves to reduce stress on the articular surfaces.

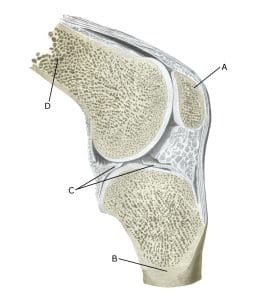

Knee joint:

A. Patella (Kneecap)

B. Tibiae (Shinbone)

C. Meniscus lateralis (Outer meniscus)

D. Femur (Femur)

Cause of the problem

Repeated strain can damage first the cartilage and then the bone under the cartilage (osteoarthritis). Osteoarthritic changes on the back of the kneecap often occur after a fall on the knee (e.g. line players in handball) and many minor overloads. Twisting the knee joint where the femur and tibia meet can cause a piece of cartilage to be repelled (osteochondral lesion), which can move around the joint (joint mouse) and become trapped (locking). In many cases, however, the cause of the cartilage damage is unknown. Weakness of the thigh muscles and obesity have been suspected as contributing factors.

In some cases, osteoarthritis changes can lead to an ‘inflammation’ of the synovium (synovitis), which causes fluid build-up, swelling, restricted movement and pain in the knee joint. Osteoarthritic changes in the knee often occur after previous ACL tears or meniscus injuries where it has been necessary to remove (parts of) the meniscus.

Many cartilage injuries do not cause symptoms and therefore do not necessarily require treatment.

Symptoms

Pain in the joint when moving with strain, especially with a bent knee, such as climbing stairs. Often there is difficulty starting, relief after warming up, but pain returns after prolonged strain. A feeling of stiffness in the knee after prolonged sitting. Occasionally there may be swelling in the joint (synovitis). With severe swelling, a fluid-filled bursa can develop in the back of the knee (Baker’s cyst).

Examination

General clinical examination is often sufficient. Cartilage damage to the back of the kneecap often causes soreness and jarring when the kneecap is pressed against the femur. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, the medical examination can be supplemented with a specialised X-ray, MRI and ultrasound scans and arthroscopy (binocular examination of the knee joint).

Ultrasound scans can detect very early signs of osteoarthritis changes.

Treatment

Treatment includes relief from pain-inducing activities, stretching and slowly increasing rehabilitation within the pain threshold. The primary goal is to strengthen the muscles around the joint and maintain joint mobility. If there is swelling in the joint (and the popliteal fossa), you can try to reduce the synovitis with anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or by draining the joint fluid and injecting adrenal cortex hormone. In some cases, there is an indication for (diagnostic) arthroscopy (or for the removal of joint mice).

There is no treatment that can restore the damaged cartilage, which has little ability to heal. For severe osteoarthritic changes with pain at rest (at night), it may be necessary to replace the joint. Various surgical methods to restore the damaged articular cartilage have been tried, but there is no convincing evidence of long-term effects (Wagner KR, et al. 2022)

Bandage

For cartilage damage to the back of the kneecap, some people have noticed an improvement in discomfort when using a knee brace to keep the kneecap slightly to the side. Kneecap stabilising tape can also be used.

Complications

If no progress is made, you need to consider whether the diagnosis is correct. It will often require additional examinations (X-ray, ultrasound, MRI scan or arthroscopy).

In particular, the following should be considered:

- Meniscus lesion

- Outer collateral ligament rupture

- Fluid accumulation in the joint

- Inflamed mucosal fold

Despite very severe changes, you will usually be able to do sports with less knee-straining activity (e.g. swimming) without major discomfort, while restraint with sports with high knee strain (running, ball games) is advised.

Especially

Shock-absorbing shoes are advisable.