Anatomy

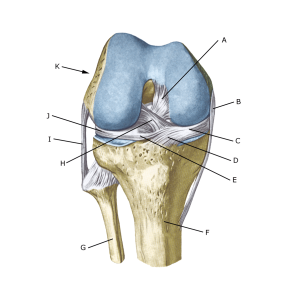

The bones of the knee joint include the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone) and patella (kneecap). There is also a small joint between the tibia and fibula (fibula). The knee joint is reinforced by a joint capsule that is laterally reinforced with an external and internal collateral ligament (ligamentum collaterale laterale (LCL) and ligamentum collaterale mediale (MCL)). Inside the knee are two ligaments, the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ligamentum cruciatum anterius (ACL) and ligamentum cruciatum posterius (LCL)).

Knee joint from the front:

A. Ligamentum cruciatum posterius (Posterior cruciate ligament)

B. Ligamentum collaterale mediale/tibiale (Inner collateral ligament

C. Meniscus medialis (Inner meniscus)

D. Insertio anterior menisci medialis

E. Ligamentum transversum genus

F. Tibiae

G. Fibulae

H. Ligamentum cruciatum anterius (Anterior cruciate ligament)

I. Ligamentum collaterale laterale/fibulare (External collateral ligaments)

J. Meniscus lateralis (Outer meniscus)

K. Femur

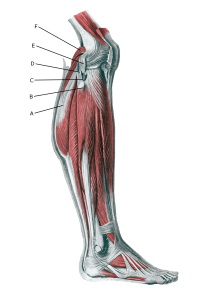

Lower leg on the outside:

Lower leg on the outside:

A. M. gastrocnemius

B. Caput fibulae

C. B. subtendinea m. bicipitis femoris inferior

D. M. biceps femoris (overcut)

E. Ligamentum collaterale laterale/fibulare (Unique lateral ligament)

F. M. plantaris

Cause of the problem

When the tibia is pressed outwards in relation to the femur (fibula, varus), the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is stretched. If the load is high enough (as is often the case if the load comes unprepared so that the thigh muscles do not have time to tense and stabilise the knee joint), the ligament can rupture.

Symptoms

Sudden onset of pain on the outside of the knee. Sometimes a pop is felt when the ligament ruptures. In severe cases, the athlete complains of a feeling of looseness in the knee.

Examination

If you suspect a total or partial rupture of the ligaments in the knee, you should see a doctor for a diagnosis. The doctor can perform various knee tests (LCL video) to examine the stability of the knee.

If the knee is stable, the injury is referred to as a ‘sprain’ or ‘partial tear’ of the outer collateral ligament. If the knee is loose, the injury is referred to as a ‘rupture’ of the ligament. The diagnosis is usually made during a general medical examination. If there is also internal looseness on the extended knee, there will most likely also be damage to the ACL.

If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, an ultrasound or MRI scan can be performed to see the tear and bleeding along the ligaments. Ses ultrasoundscan here

X-rays are recommended to rule out fractures if the athlete is under 12 years old or over 50 years old, if the pain is so severe that the athlete cannot walk 4 steps without pain, if the athlete cannot bend the knee more than 60 degrees or if there is localised bone tenderness (‘Pitsburgh Knee Rules’).

Treatment

Treatment for total or partial tears of the lateral collateral ligament includes offloading and rehabilitation. If the knee is severely loose, a support splint (Don-Joy) can be used for a short period (a few weeks) to allow free movement and full support of the leg. Movement training is started immediately. In cases of total rupture and pronounced looseness without progress with training or combined with other injuries, surgery (reconstruction) may be indicated.

Bandage

A hinge bandage can be used briefly at first (Don-Joy). Tape treatment of knee ligament ruptures is often used, but there is little evidence of effectiveness.

Complications

Treated LCL lesions have a good prognosis and rarely cause problems. If no progress is made, you need to consider whether the diagnosis is correct. This will often require additional examinations (X-ray, ultrasound and MRI scans or arthroscopy).

In particular, you need to consider:

Especially

As there is a (modest) risk of permanent injury, the injury should be reported to your insurance company.